Happy Mother's Day!

Happy Mother's Day to all the women who birth, care, nurture, and shepherd life. Whether that life is of your own blood, of your own heart, human, or fur, you are honored today!

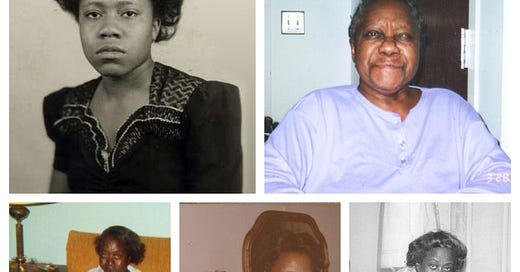

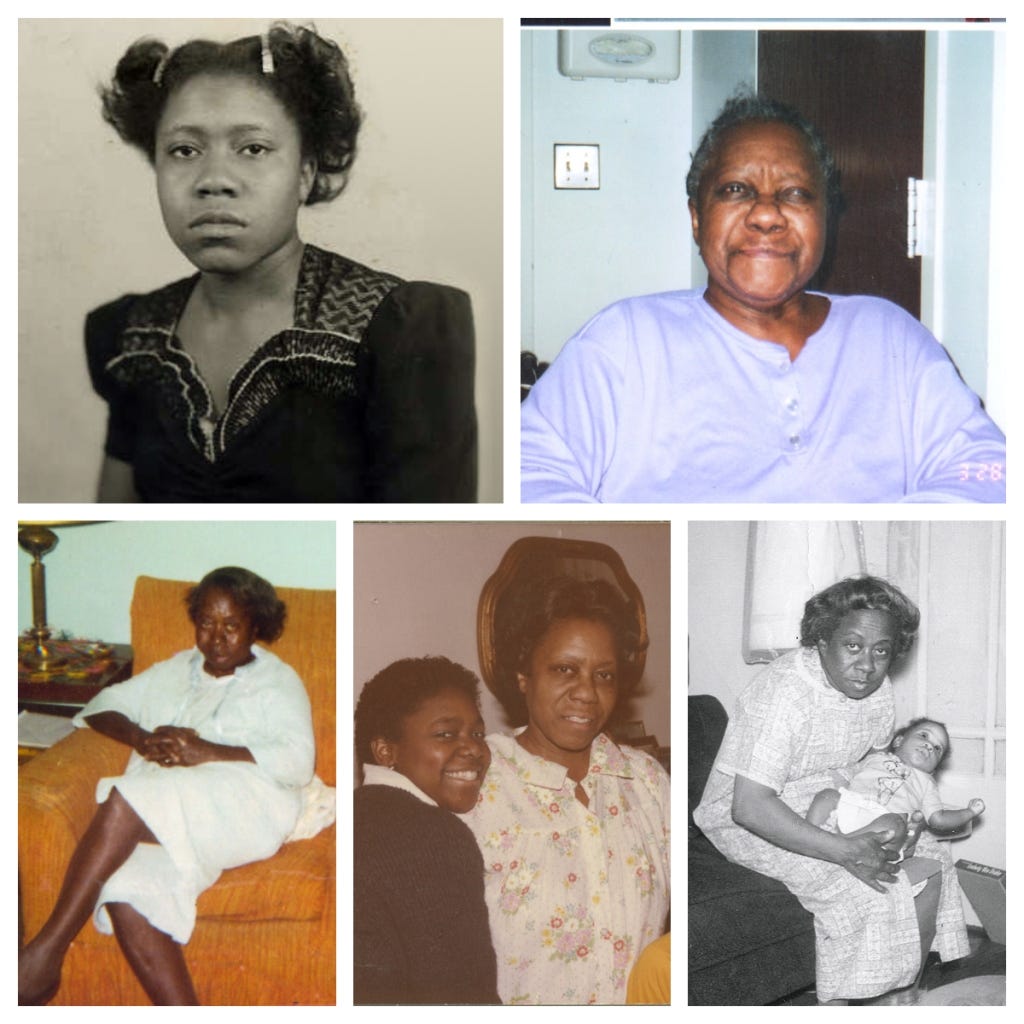

I wrote a memoir what seems like eons ago. It is yet-to-be published, and with this much space between the last time I pitched it and now, it will probably need ample rewrites and of course, new content. But, there are certain chapters of which I am quite proud: and this chapter about my own mother, Bernice Oliver, and the matriarch of our family, Annie Foxx is one of them.

An excerpt about mothers and grandmothers, on this day to honor the mother's in your life and world.

Excerpted from Fried Chicken and Sympathy, Chapter 1: Affectionately Known as Bay

My mother’s given name was Bernice Betty Jo Foxx, but everyone called her “Bay.” Born on August 10, 1931 in Tyronza, Arkansas, she was the fifth of the eight children born to Annie Belle Simmons Foxx and Joe Henry Foxx. Tyronza is one of those towns that if you’re driving through it and blink, you’ll miss it. It borders on Arkansas and Tennessee, and its population today is just over 1,000. That’s the number of people in a four-block radius in most major cities. The small-town ethic of family, religion and community remained a part of Bay all her life, even though she lived most of it in big cities. But Bay was never really happy in the city, and spoke often about moving back down South.

Bay was a beautiful girl, with what we would call a “high-yella” complexion. This was sometimes a point of teasing between her and her sisters, who were much darker than she was. She had curly brown hair that she wore short to frame her face, and she had a petite figure that was made for the fashions of the ‘50s and ‘60s. Two pictures of her that always stick in my mind are her eighth-grade and high-school graduation photos. In her eighth-grade photo, she is standing in a shin-length white petticoat dress, and white strappy shoes découpage shoes. Along with the white corsage, she wore a stoic expression which would later come to characterize her general demeanor. Her high-school graduation photo was much more carefree, even happy—which is a term I would rarely use to describe my mother. It was a head and shoulders portrait, in her mortarboard and robe, and Bay has her head posed to the side, with an upturned smile, as if looking forward to the future. That picture gives a glimpse of the Bay I never knew, and the Bay that probably attracted my father, Oliver, to her. Unfortunately, the years of death and destruction, beginning with his murder in 1970, wiped that woman completely out, and only the picture is left to bear witness that she ever existed.

Bay and her seven brothers and sisters picked cotton for extra money, while Grandpa Joe worked in a mill, and Grandma Annie cleaned houses and raised chickens in order to sell the eggs. When Mom was in the fourth grade, they moved to Memphis, where they had greater work opportunities.

Tyronza was a spit in the dirt compared to Memphis. Grandpa Joe worked as a houseboy at the once-prestigious Peabody Hotel, and also at the King Cotton, and Grandma Annie worked as a maid at both hotels.

My Uncle Joe Louis, Bay’s youngest brother, added, “Grandpa was a ‘sharecropper’ in Arkansas, so moving to Memphis and getting a job in a hotel was a step up. And believe it or not, it was also easier work.”

With Grandma Annie working nights, my mother went to school during the day and worked during the evening, sharing the responsibility of caring for her toddler brother (Joe Louis) with her sister Cornell (Honey). She graduated from eighth grade, and went on to Washington High School, while working nights in a hospital. When today’s teenagers talk about the pressure they’re under to make good grades and work at the same time, I shake my head. Bay made exceptional grades and worked pretty much full-time—concrete proof that one can do what one sets one’s mind to.

Being the third girl, Bay was closest to her older sisters, Geraldine and Cornell, or “Honey,” as I came to know her. As my Aunt Allene, who was born after Bay, attests:

“Of course we were close,” she said. “We argued like most siblings, but we didn’t fight. Mama didn’t allow that.”

The Foxx way of hard work, family and sacrifice was part of Bay’s genetic code, and was passed down from her unique and visionary parents. Uncle Joe Louis elaborates:

“Based on what I heard and saw, they had a difficult time in the South. By ‘difficult times,’ I am only referring to what was most likely a universal state of affairs for Blacks in the South at that time. Most had large families and low-paying or no-paying jobs. There was never enough money. In the case of Daddy, it was a no-paying job.”

Uncle Joe elaborated on what this type of “employ”—sharecropping—really entailed: “A person lives on someone’s farm, and plants and harvests the crops for a share of the profits when they are sold, but this was the replacement for slavery. They were owned economically, because after the crops were sold, and the profits divided, and the indebtedness paid, there was usually very little left for the sharecropper—so the cycle started all over again with an indebtedness.”

Grandpa Joe Henry and Grandma Annie Belle both had the wit and wherewithal to move out of a no-win situation, in order to attain a better life for themselves, and their children, and they were strong influences on their children and grandchildren—but Grandma Annie, in particular, left certain distinctive marks on Bay.

Grandpa Joe Henry’s grandmother had been a slave, and somewhere in the lineage we have Native American—most likely Cherokee or Blackfoot-blood, although Aunt Everette, Bay’s baby sister, says that we also have Crete in our line. Grandpa Joe had that burnished mahogany skin, hooked nose and chiseled countenance that is typical of Native Americans, and it shows in the black and white photos I have of him. Annie Belle was also the granddaughter of slaves, and was a proud woman who kept a clean home and was no-nonsense about almost everything. Her life revolved around her children, her church and her community; she took these things seriously, and expected everyone around her to do the same.

Bay inherited the no-nonsense persona from Grandma Annie. Silly and lazy just didn’t rate in her book. You were either about business, or you were up to no good. When my sisters were younger (somehow, the brothers were exempt), Saturday mornings always started early, doing laundry, cleaning and ironing. One of Bay’s constant expressions (I’ll call them “Bayisms”), was, “An idle mind is the Devil’s workshop!” I’m quite sure she heard this first from Grandma Annie’s mouth, and she definitely learned under her tutelage to never to be idle.

Annie stood 4 feet 11 inches tall, but according to those who knew her, she packed a wallop. She’d go on tirades without warning, and the whole house would shake. My cousin Ricky called them her “5150 episodes,” borrowing the police code for someone having a psychotic breakdown. Her storms ranged from swearing up a blue streak to throwing pots, pans and any furniture that wasn’t nailed down.

Since she died before I knew her, most of the information I do have is thanks to my brothers, sisters and cousins.

Some of that fire is just the Foxx nature, but I also suspect that Grandma Annie’s short fuses were due to brain damage. She’d had a stroke in 1958, which left her partially paralyzed on her left side. But Annie had a strong will, and refused to let it immobilize her. She regained her speech, and with the help of a cane, she was able to walk and get around quite well. Although she couldn’t work full-time, she still tended to the house and her family.

Where Grandma Annie was volatile, Grandpa Joe was as even as a river in summer. A calm, peaceful man, he was happy and smiling, always humming a tune—especially when Grandma Annie went 5150—which only irritated her more. But the more she fussed, the more he hummed and sang. Guess everyone has his way of coping, and that was his. He died from brain cancer a week after I was born. Bay started keeping a family history in 1983, and she wrote this about Grandpa Joe’s death: “August 1966 was the death of my father and the children’s grandfather. He was missed very much. He died of cancer, starting with a kidney that had to be taken out and it spread to his brain. After they operated, he passed away.”

June remembers Bay breastfeeding me at Grandpa Joe’s funeral, a towel draped over her shoulder for modesty. So I guess you can truly say my life began with death.